I’ve run a few Forged in the Dark-style games in my time and every once in a while someone in my gaming circle expresses some desire to know what I’ve learned from these experiences. I’ve been GMing one game or another for about 25 years now and even though I’m certainly not the most experienced Blades in the Dark GM in the world, I do think my accumulated experiences give me some insight into what works well in these types of games, and why it works. For whoever this may interest, here is an outline of how I run these games, and why I do what I do.

Campaign Structure

When kicking off a new Forged in the Dark campaign, before even sitting down with the players, I start by putting together a few ideas about active conflicts in the setting, as well as a few ambient threats. For the active conflicts I want one between the major factions in the setting (maybe a group of industrialists are laying political siege on the city council), as well as a conflict closer to home for the players (in Blades, the classic example is the turf war between the Red Sashes and the Lampblacks). The players are obviously more than welcome to introduce their own conflicts, but having some pieces moving in the background both gives life to the setting and gives me as the GM hooks to throw at the players if things slow down.

Ambient threats are trickier to weave into the game, but I like to have a couple extra things in my back pocket just in case. Examples could be a cult being secretly led by a demon, a sect of Spirit Wardens who want to hollow the citizens of Doskvol in order to all but eliminate the threat of ghosts, or a blight affecting the fungus farms and threatening the city’s already limited food supply. These threats can be big or small, localized or diffused, but the idea is to have something that I can pick up and weave into some other situation to punch it up if need be.

However, I’m holding onto all of this very lightly until I have a session zero with the players. Once I have a chance to get everyone together and do character and crew creation, and get a feel for what the players want to be doing in this world, I get a firmer idea of which parts of my prep to either get rid of or push to the foreground. It’s also at that point that I pick a few more factions to actively keep track of between sessions in order to liven up the setting.

At no point yet have I given any thought to what the “story” of the campaign is going to be. I do like to break up my games into 12-ish session long “seasons,” but I don’t start out knowing what the arc of that season is going to be; usually, the players will cause enough of a ruckus and make enough enemies within the first three or four sessions that they do the heavy lifting for me, and the rest is just playing out the situation they’ve made for themselves.

Once the campaign is on its feet, I generally try to push the players to come up with their own scores, but because I’m always tracking a handful of NPC factions—more on that later—and therefore know what they’re up to and what they want and need, it’s never too difficult to come up with a job for the crew if they solicit one. And if doing a job for an NPC faction embroils them is some broader conflict, well, all the better.

Note what I haven’t said here: I don’t plan a bunch of stuff specifically around the players’ crew. To my mind, the crew is the players’ responsibility, and I tell them that explicitly. If they want to build out the crew, I’m totally on board to play in whatever direction they want, but I don’t want to do that for them, same as I don’t want to build their character for them. I run the world around the players’ characters and crew, and it’s on them to figure out how they’re going to fit into it (or carve out the space they want).

Session Structure

Blades has a built in session structure—free play/score/downtime—but within that structure there are still a lot of ways to play the game. John Harper is famous for running very abbreviated downtime/free play phases and getting to the “action” of a score as quickly and as often as possible. I, on the other hand, tend to run my games at a much more leisurely pace, usually only running a score every other session, with a whole session between each of those usually devoted to free play—checking in on NPCs, detailing various projects the PCs are working on, etc. If you’re new to GMing Blades, you’ll have to figure out what pace works best for you and your players.

During a session, it’s not uncommon for all of my players to be up to something different, sometimes even during a score, so something I always keep front of mind is which of the players hasn’t had a chance to speak in a moment. This means keeping the action moving at a decent clip for each player so no one is waiting for their turn for too long, but it also sometimes means pausing a scene with one player to check in on another.

When my players ask if something is possible or attainable during a session, I pretty much always say, “Yes,” and then think of an appropriate cost. A ritual that will bind a demon to a sword? A rod that shoots bolts of electricity? An elixir which allows one to traverse a weird dream realm? Sure, let’s figure out how to do that! Maybe something needs to be researched, maybe something needs to be bought, maybe something needs to be stolen—maybe there’s some darker, more eldritch cost. But yeah, sure, let’s do it. I avoid trying to come up with this stuff on my own, I prefer to talk it through the with interested player.

Every few sessions I also like to check in about the crew’s broader agenda, if they’ve established one. Does the goal remain the same? Do we feel like we’re making progress? What’s next? It’s good to make sure I’m on the same page as the players.

Other than that, I’m just doing my best to follow the PCs around the world. Sometimes the players know what they want to do, sometimes that means I say things like, “Hey, it’s been a while since we checked in with that vampire you know, should we see what he’s up to?” and leave it up to the player if we follow that thread.

Factions (and Threats)

Let’s talk a little more about factions! Factions as presented in Blades are very simple and flexible, essentially amounting to a collection of free-form tags, which means it’s easy to keep them super minimal or add to them whatever helps you prep and run the game. I don’t go too wild with it—I have toyed with layering on a Stars Without Number style faction system, but have yet to get around to it—but I do have a couple little extras I like to play with.

A GM tool from Apocalypse World that I love is “threats,” which in a lot of ways are very similar to factions in Blades. In Apocalypse World, anything which could possibly threaten the safety of the PCs gets written up as—you guessed it—a threat, which generally amounts to an impulse and a handful of moves. Basically the idea is to write yourself a simple script to follow if you’ve ever not quite sure how it would respond in a given situation, and I love that! When running Blades, anytime a faction becomes important to the players, I write up a couple threats associated with it using the basic structure straight from Apocalypse World.

I usually have NPC factions try to ally with the players’ crew as their opening move, unless they are obviously in opposition. I like doing this because if the players are receptive, that NPC faction’s enemies now consider the PCs their enemies as well, and if the players rebuff the proposed alliance, their would-be allies now have a grudge against them, and either way this new set of relationships is fairly easy to understand. From that point forward, I keep track of how the PCs treat the NPC factions they’re in contact with. Do they keep their promises? Do they have their ally’s back? Do they fuck people over left and right? I think it’s fun when NPCs have long memories.

As for surfacing information about the faction game to the players, a lot of it is just in-game rumors and gossip, with NPCs more or less constantly furious about what their enemies are up to. I’ve also sometimes written in-universe news headlines or news briefs, which my players have loved.

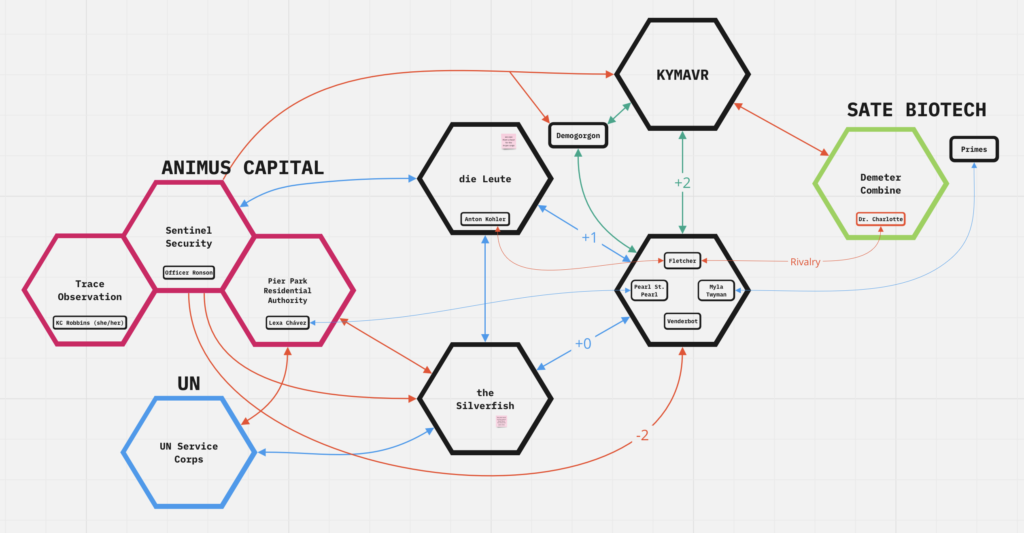

Another tool I’ve used to communicate faction relationships to players is what Paul Beakly of The Indie Game Reading Club calls an “R-Map,” which he actually recommends not using for Blades, but I think the way I run these games leans more on the interconnected relationships and is less strictly mission-oriented that he supposed in his post. Certainly, for some groups, an R-Map is too much detail, but I find it helps players keep all the moving pieces—and therefore all the levers available for them to pull—in mind when deciding what moves to make.

Action Rolls, Position, and Effect

I don’t know how others adjudicate actions in Blades, but here’s how I do it: the default rhythm of the game play is me as the GM describing the fictional situation and then asking the players what their characters do, then describing the new situation, and so on and so forth. When a player describes an action about whose effect on the current situation I am not exactly certain, we start negotiating an action roll.

Usually, this starts with me saying something along the lines of, for example, “Okay, I think this calls for a roll, it sounds like you’re Swaying, is that right?” The player might then say, “Sure!” or they might look down at their character sheet and say, “Eh, no, I want to be Commanding,” but one way or another we figure out what action is being used.

Next, I decide the initial position and effect level for the roll. Usually, this is the default: risky/standard. For position, I instead start at controlled if there’s no immediate threat, but I can imagine the situation snowballing, or desperate if there is some immediate and significant threat present—for example, essentially all melee combat situations are desperate. If you would be setting the position at controlled but can’t see how the situation would snowball beyond the current action roll in question, now is probably the time to ask yourself if a roll is even necessary. Perhaps if you still think there ought to be a roll, it’s a fortune roll instead of an action roll, in which case you don’t need to negotiate position and effect—I sometimes like to call for some kind of fortune roll upon meeting a new NPC just to gauge their initial impression of the crew, similar to a mien roll in some other games.

I fiddle with the effect level less often, usually leaving it at standard. Exceptions would be when scale is involved, or when there is an obvious significant advantage on one “side” of a roll. For instance, if a PC has a magical sword and is Skirmishing with a rank-and-file thug, the PC probably has great effect; however, if they are fighting a small group of thugs, the scale roughly matches the advantage of their magical blade, dropping their effect level back down to standard.

Setting initial position and effect can be tricky even for people who broadly enjoy this system, but I suspect for people who dislike Blades, this what they bounced off of. However, I love this part of the game and am of the opinion that it simply makes explicit a dynamic that exists in unspoken or implicit form in nearly all role-playing games. The text of Blades offers a lot of guidance on this, and as helpful as that can be, my advice to new GMs is to not overthink it in the heat of the moment—just go with your gut and negotiate from there.

Because—and this is the most important thing about all this—I do think position and effect should be up for negotiation before anything gets rolled. If I say, “You’re Skirmishing a group of thugs, they outnumber you three to one, so your effect here is limited,” the player might rightfully say, “Oh! But the Dimmer Sisters enchanted my blade, that’s got to help me here, right?” and we might go back and forth like that taking factors into consideration and talking through the specifics of the action until everyone agrees everything’s accounted for, and only then does the player roll.

Two notes on this. First, neither player nor GM should forget that the specific action being rolled is also up for negotiation. Second, it should absolutely be possible for a player to negotiate themselves out of making a roll at all—if in talking through the situation everyone realizes we pretty much know exactly how the situation unfolds without the need for a roll, then that’s that.

Once the dice have been rolled, factor the result into the position to determine consequences impacting the character, and then factor the result into the effect level (and consequences, if applicable) to determine how successful the character was with their action. For instance, in the previous example of a PC with a enchanted blade fighting a small group of thugs, if we ended up settling on a position and effect level of desperate/standard, and the die result was 5, the result would likely be something along the lines of the PC has slain the thugs, but sustained a serious injury (level 3 harm) in the process (which of course they are welcome to resist).

Something I also like to do at this stage when it makes sense is offer a player a worse consequence for greater effect. For instance, if the PC in the example above didn’t have that enchanted blade, their position and effect level likely would have been desperate/limit—not great! But if they pressed onward, and then roll a 6, then they dance between the blades of their enemies, landing a few blows where they can. But they only had limited effect, meaning the fight’s not over—it’s at this point I might give them the option of opening themselves up to harm in order to get those last few critical blows against their enemies. If they go for it, then like last time, their foes are slain but they take a level 3 harm in the process.

As an aside, something I see sometimes in online discourse around Blades is a version of the classic (note: derogatory) “role-play vs. roll-play” debate, wherein an observer looks at the Blades text and notes that the action menu encompasses most things you might imagine doing in the game, and imagine that Blades’ game play must therefore be solely composed of a string of random die rolls. (And, in case it needs to be stated, in this imaginary scenario, crossing the invisible and arbitrary line into rolling the dice “too much” means that a game is bad, and maybe even not really a role-playing game.) This is, of course, completely idiotic.

On Quantum Ogres

A criticism frequently leveled against essentially any system which involves open-ended die roll outcomes—especially if there is also an “intermediate” level of success possible rather than binary success/failure—is that this inevitably results in “quantum ogres.”

For the uninitiated, a “quantum ogre” is shorthand for any situation in which a threat is suddenly thrust upon the players regardless of what choices they’ve made up to that point. The term originates from the idea that in a dungeon crawl, if there’s a corridor to the left and a corridor to the right, and an ogre somewhere in the dungeon, that ogre should definitely be at the end of either one or the other corridor; if the GM decides that the ogre happens to be at the end of whichever corridor the players happen to head down, the GM has robbed the players of making a real choice—that’s a quantum ogre. (A couple things that go unstated are that the players have only been robbed of making a “real choice” if they first had enough information to actually distinguish between one corridor and the other, and second if this is even a category of choice which bears any significance to the players.)

In the context of Blades and similar games, the specter of the quantum ogre is invoked by pointing at failures and mixed successes and proclaiming, “See, when you roll the dice, anything can happen! It’s completely up to the GM!” Hopefully, if you’ve read this far, you already see how farcical this is—if you’re playing Blades even remotely like I do (which is to say, even remotely as described by the text itself) then you and your fellow players are talking through the stakes of a roll before even touching the dice, and generally allowing for backing out of a roll completely and trying something else if the stakes aren’t to a player’s liking.

There are some instances where I might spring something unexpected on the players, with some caveats. In the first instance, if the players are infiltrating a space I know to be patrolled or otherwise occupied by hostile forces, generally the first encounter with these patrols will be to start a clock counting down to the hostiles going on full alert. Second, if the players have pissed someone off, I might decide they’ve sent out some goons to rough up the PCs, or maybe even put out a contract on the life of a PC—either of which the players might or might know about ahead of time depending on the contacts they cultivated or how defensively they play—but from that point forward I know they’re being hunted, and their pursuers might take any moment of weakness to strike. (On the other hand, if a PC scores a critical success, telling them they notice they’re being followed is an easy little bonus to through their way!)

Clocks

I make frequent use of clocks, as I think most Blades GMs do, but there are two notes to call out here.

First, I treat clocks as purely descriptive. This is exactly how they are presented in the text (Blades in the Dark, p. 15), but the way they are often discussed leads me to believe that in practice they are more often treated as prescriptive—that is, an obstacle is only resolved when the corresponding clock is filled, and that clock only fills in response to action rolls. Instead, I treat clocks simply as ad hoc trackers for the fictional situation, which does still mean that action rolls affect clock states, insofar as action roll outcomes affect the fictional state, but I also update clocks in response to any shift in the relevant situation. For instance:

- If the crew is infiltrating a rival faction’s headquarters and one of them tries to stab a guard in the back, we might resolve that with a Prowl roll and depending on the outcome of that roll I’d update an Alert! clock. However, if the crew decides to snipe the guard with a rifle, regardless of whether we call for an action roll, their rivals are now alert—I don’t need a die result to tell me that, the new fictional situation is that the report of a rifle has sounded and everyone heard it!

- If the crew is trying to negotiate a border between their territory and a neighboring gang, I might have a clock tracking the progress of that negotiation, to which crew members might contribute with the Long-Term Project downtime activity, or in any number of other ways that either strengthen the crew’s territorial claims or improve the diplomatic situation. If they fill the clock through these incremental measures, that signals to me that their neighbor is ready to conclude negotiations and draw the line. However, the crew might at any time during this period press their claims and call for an end to negotiations—the leadership for both the crew and the neighboring gang meet up, at which point I would probably stop using the existing negotiation clock to track progress, but I would use their progress on that clock as a rough measure of how many more concessions to which the other gang thinks they are entitled.

Again, this approach to clocks is not my own invention, it is how the text of Blades presents clocks. I only go into this detail because I think many GMs take a much more prescriptive approach to clocks, with frustrating results.

Second, okay, cards on the table, there is one situation in which I do break my own rule: if and when a long-term, looming threat to the crew develops, and I decide to track it with a clock—what the Blades text refers to as a series countdown (Blades in the Dark, p. 206)—I like to attach a few “triggers” to specific stages of the clock, and the further along the clock gets, the harder it gets to divert the force behind it. This is inspired not by Blades, but by Apocalypse World‘s countdown clocks (Apocalypse World 2nd Edition, p. 117–118). In Apocalypse World, countdown clocks are attached to threats, much like the faction clocks of Blades, and when they reach certain stages, that signals to the MC that the threat performs some decisive action which shifts the fictional situation. For instance:

- If a revolution is brewing in Doskvol, I might have a Revolution! series countdown clock tracking the rise and fall of revolutionary fervor. The crew might contribute one way or another to that clock, as might other factions in the city. The crew might be aware of the clock and its current progress—after all, they can feel the political tension in their bones like everyone else—but they might not be aware that once the clock reaches the 50% mark, one of the revolutionary-aligned gangs will bomb a Bluecoat precinct house. However, depending on how involved the players’ crew is, they might know about this plot beforehand, or might even be the ones asked by other revolutionary factions to carry out the plot. Additionally, once this stage is reached, revolutionary fervor can no longer simply quietly dissipate—either it boils over into a full-blown revolution, or it ends in overwhelming state violence against revolutionary factions.

- Let’s say a botched cult ritual has torn a hole in reality and threatens the engulf the entire city. Every downtime, I roll randomly to see how much worse it gets. Maybe there are ways to mitigate its progress, but I know those methods only work up to a point—once the clock exceeds 50%, half-measures no longer work. There is a ritual to seal the fissure for good, but again, if the damage has exceeded the 50% mark, the ritual must be performed from both sides, permanently sealing at least one person in another world. And finally, if the damage exceeds the 75% mark, sealing the fissure also destroys an entire city block as a riot of celestial energy is released.

I use this structure sparingly, and always leave myself room to imagine the players doing something completely unexpected and upending what I’ve written next to my clocks, or at the very least discovering what’s to come and planning ahead.

A Note on Directionlessness

The Blades (and other Forged in the Dark) games I’ve played sing for players who have very clear drives and who actively pursue those drives. With that said, it should come as no surprise that if a group of players lacks a certain critical mass of driven players, things… start to get a little weird.

When you’re playing a dungeon crawler, it’s sort of tacitly understood that character motivation is entirely optional. After all, we all know what we’re supposed to be doing here: fighting monsters and stealing treasure. Anything a player chooses to layer on top of that is just a little extra flair. Some players might bring these play expectations into a Blades game, which will end up looking like a lot of waiting around to be given a mission by an NPC and not engaging in any faction-level politicking.

If only one or two players operate this way, the game still might run fine, with the caveat that you’ll almost certainly be spending more time on the players’ characters who are engaging with the more character-driven aspect of the game.

The real issue is that if most or all of your players are playing this way, you as the GM can quickly end up feeling like you’re playing by yourself. An NPC will give the players’ crew a mission that furthers that NPC’s interests, which shifts the faction situation, but your players probably don’t really care about that, so the biggest response to that shift will be… other NPC factions. So the game becomes you managing a little ant farm of factions and NPCs in which the players occasionally do something, the effects of which only you really care about.

I don’t think there’s any way to fix this, because nobody’s really doing anything wrong per se, it’s just that the players don’t really want to be playing the game you’ve brought to the table. So the fix is really just to play something less character-driven.

A similar but slightly different issue arises when the players don’t feel any particular connection to their crew, mainly because it’s really easy to prep hooks for players who are very engaged with their crew, and not having that makes your work as GM harder. For example, if the players choose to be Hawkers and they get really into selling illegal alchemical components, it’s pretty easy to know what types of rumors, job offers, rivalries, etc, will get the players excited. Conversely, if the players choose to be Hawkers and then show no interest in selling anything in particular, well, that doesn’t give you a lot to work with.

This second problem might exist on its own, in which case I think it is fixable by discussing it openly with the players, but it might also be merely a symptom of character-level directionlessness, in which case, again, I don’t think it’s something that can be fixed.

Things I’ve Tried (and Things I’ve Yet to Try)

I’ve tried a few little experiments over the years in my Forged in the Dark campaigns, some of which have had pretty positive results.

Prequels

Because the way I run these games leans heavily on a network of faction relationships, making sure the players have a strong understanding of the setting before creating characters and crew can be very helpful. The best way I’ve developed to ensure this is to play a handful of “prequel” games in that setting. This idea is inspired primarily by the Friends at the Table actual play podcast, which did this exact thing in the lead up to their “Partizan” season (the prequel series was entitled the “Road to Partizan”).

The prequel games I’ve run have been structured as a series of one-shots and don’t follow a single through-line, but rather come at the setting from a bunch of disparate angles in order to fill out as much as possible. They also tend to be GM-less games, in which I interject as little “canon” setting information as possible in order to invite the players to help shape the setting.

The games I’ve used so far for these prequels are:

- Kingdom, by Ben Robbins

- The Quiet Year, by Avery Alder

- Endure, by Fred Bednarski

Any game that would make for a good one-shot could be run as a prequel game. My players and I enjoyed these prequels quite a bit.

Asides

Surely once we’ve played through the prequel series and have the main campaign up and running we just play that though, right? No! Something I love doing is having little asides in my larger campaigns where we jump out of the main action and see what’s going on somewhere else.

- I once used a hack of Trophy Dark, by Jesse Ross, to play through a Blades PC’s dream quest through a strange nightmare realm.

- In that same campaign, the PCs asked a vampire friend of theirs to cause a diversion for the Spirit Wardens, which he did by tricking the Red Sashes into disrupting a dangerous cult ritual and causing a massive magical catastrophe; we played through this mission with the Red Sashes using World of Blades, by Duamn Figueroa Rassol.

- In my hacked cyberpunk game, we were down a player one session and instead of playing the main game we played a queer enclave just outside the city walls with Dream Askew, by Avery Alder.

I love playing these asides, and will continue to do them as long as my players will indulge me! I really want to hack Trophy again to run an expedition into the Deathlands in a Blades game.

NPC Crew Leader

This is one I haven’t actually tried yet, but I’ve been really wanting to see if it could work. Here’s the problem it intends to fix: with a group of new players in an unfamiliar setting, it can be tough for them to find their footing in the system and in the world. There are plenty of ways to mitigate this, but what I sort of want is a more structured “tutorial” mode. So what might that look like?

The idea I’ve been toying with is having the player crew start the game essentially owing fealty to an NPC faction. The players can take jobs on their own, but are largely expected to follow orders they receive from their bosses. This gives me as the GM license to plan out a handful of introductory missions while the players get their bearings.

Now, I suppose the players could choose just to be good soldiers for their bosses, but I suspect that would get old pretty fast. My expectation would be that the players eventually rebel against their bosses and fight for their independence, which I think would be pretty fun for everyone involved. Maybe I’ll pitch this to my players next time I run one of these campaigns!

A Final Thought

I really like Blades in the Dark. I cut my teeth DMing Dungeons & Dragons 3rd Edition and various iterations of that game remained my bread and butter for over 10 years. Encountering Apocalypse World and Monsterhearts began a shift in my gaming sensibilities, but it wouldn’t be until I started running Blades that it felt like I found something that really clicked, and now my experience running Blades informs all my GMing, regardless of the game I’m playing. If you’re just beginning your journey as a Forged in the Dark GM, I hope I’ve been able to share something that help you on your way.

Leave a Reply